Your cart is currently empty!

Why We Need Aldo Leopold’s ‘Land Ethic’ Now More Than Ever

An ongoing reckoning with race in American history has drawn attention to racism in the environmental movement. Critiques have focused on themes such as forced removal of Indigenous peoples from ancestral lands, early conservationists’ support for eugenics and the chronic lack of diversity in environmental organizations.

They also have scrutinized the racial views of key figures such as John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt. Critics argue that these men valued pristine lands but cared little about poor and Indigenous people who occupied them.

Some observers say the same about Aldo Leopold, born Jan. 11, 1887. Leopold was a prominent conservationist who wore many hats – author, philosopher, forester, naturalist, scientist, ecologist, teacher. Because he was devoted to protecting wilderness and also expressed concern about the social and ecological impacts of human population growth, detractors have called him a callous misanthrope at best and racist at worst.

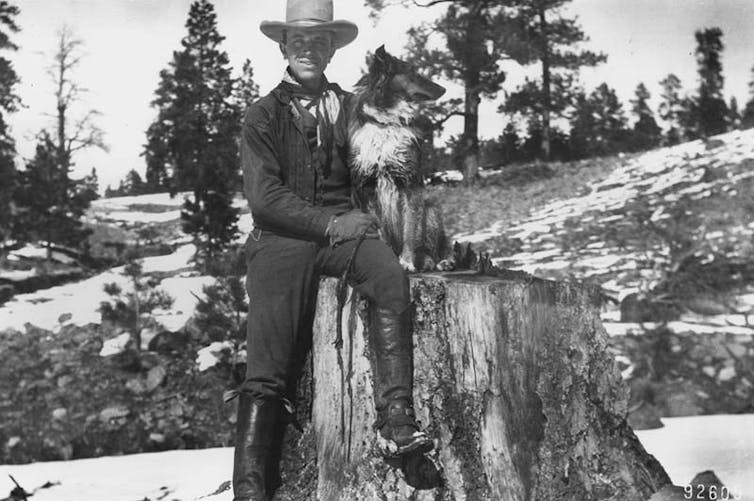

J.D. Guthrie/Forest History Society/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

As a Leopold biographer, conservationist and historian, I think this argument misses the mark. It’s true that Leopold did not fully acknowledge the historic trauma of Native American dispossession and genocide, or explicitly recognize how the impacts of land exploitation fell disproportionately on the poor and on Black and Indigenous people and people of color. But he came to believe that Western ethical frameworks had to expand to embrace land, as he wrote in his book A Sand County Almanac, as “a community to which we belong.” He called this idea “the land ethic.”

Caring for land and people

Aldo Leopold was a transformative figure in the evolution of conservation in the U.S. and globally. Trained as a forester, he contributed to the development of fields ranging from soil conservation and wildlife ecology to environmental history and ecological economics.

Early in his career, while working for the U.S. Forest Service in the 1920s, Leopold argued for protecting roadless public wildlands – what would come to be designated as wilderness four decades later – as a novel form of land use. Automobiles were just entering the landscape, and the federal government had begun funding road and highway construction across the country. Leopold pushed to give roadless lands special protection that left them open to hunting, fishing, camping and other uses compatible with their less-developed character.

Jason Crotty/Flickr, CC BY

Leopold’s rationale for wildland protection would later evolve to embrace a broader range of cultural, scientific and spiritual values. But he could only dimly foresee how wildlands would come to provide the basis for revitalizing communities and cultural connections, from Wisconsin prairies to Southwest deserts to German forests and beyond.

But Leopold’s conservation thinking never focused exclusively on wildlands. He worked to integrate land protection with care for more populated landscapes, from farms, forests and rangelands to whole watersheds and urban neighborhoods. He acted to repair damaged ecosystems and rebuild depleted wildlife populations, providing foundations for such modern fields as ecological restoration, landscape ecology and conservation biology.

A Sand County Almanac was published in 1949, a year after Leopold’s death. It is required reading in many courses on U.S. environmental thinking. I believe this is because of its lyrical prose but also because it connects the older conservation movement and contemporary environmentalism.

In the broad arc of Western conservation history, the land ethic represented a move away from viewing land as a commodity to be exploited and toward something more aligned with Indigenous views on intergenerational obligations and human kinship with other species. I believe it may contribute to further progress in realizing an ethic of responsibility and reciprocity among people, and between people and land.

Leopold, race and conservation

Several recent articles and commentaries have characterized Leopold as a racist or white supremacist. This view reflects particular claims that pertain not only to Leopold as an individual but to the conservation movement generally.

As I see it, labeling Leopold racist oversimplifies his wilderness advocacy and his effort to understand human population pressure as a factor in environmental change. It also fails to appreciate critical shifts in Leopold’s ethical outlook in the final years of his life. In his draft foreword to A Sand County Almanac he wrote: “I do not imply that this philosophy of land was always clear to me. It is rather the end-result of a life-journey….”

As Leopold was an early leader in the development of population ecology and wildlife management, it’s not surprising that he considered whether these fields could offer perspective on human population growth. He knew this was sensitive territory, and explored such notions cautiously, looking at population and how it interacted with affluence, consumption, education and technological change.

In encouraging citizens to be more mindful about their consumer choices, he redefined conservation as “our attempt to put human ecology on a permanent footing.”

The land ethic and social evolution

Although Leopold never advocated harsh or coercive population control measures or steps that could be viewed as racially motivated, he was not as visionary on social justice matters as he was on conservation issues. In his extensive writings you can find occasional statements and phrasings that now read as awkward, inept and naive. In an essay on pine trees, for example, he employed an archaic stock phrase, flippantly remarking that white pines “adhere closely to the Anglo-Saxon doctrine of free, white, and twenty-one.”

However, Leopold was also a lifelong reformer who understood the fundamental connections between social and ecological well-being. Based on that understanding, he worked to advance an ethic of care that united humans’ need for justice and compassion toward one another and toward the living land.

The land ethic as Leopold framed it was not elitist or exclusionary. It explicitly embraced people as members of the “land community,” without placing conditions on that membership. Its tenets inherently subvert racist and white supremacist attitudes.

Leopold composed “The Land Ethic” in the summer of 1947 as the clouds of World War II were still dissipating. Global conflagration and the deployment of destructive new technologies tempered his characteristic progressive outlook. He wrote – albeit in the gendered language of the time – that “It has required nineteen centuries to define decent man-to-man conduct and the process is only half done; it may take as long to evolve a code of decency for man-to-land conduct.”

Leopold saw that an ethic had to be a collective cultural effort, ever emerging “in the minds of a thinking community.” Today, as people around the world struggle to address complex and interconnected social and environmental crises, our shared future depends on forging an ethic that integrates diverse voices, belief systems and ways of knowing.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

***

GIVE YOURSELF THE GIFT OF ANALOG